Page 2 of 7

In about a quarter of an hour from this time, and about half-past two o'clock in the afternoon, she was seen to be settling down, head foremost. It is impossible to describe the wild excitement that prevailed at this moment. The lifeboat, it was expected, would be launched every moment. On every hand persons were to be heard anxiously enquiring the reason for the delay in launching the lifeboat. On, however, sped the swift-winged minutes, and no sign of the boat being launched.

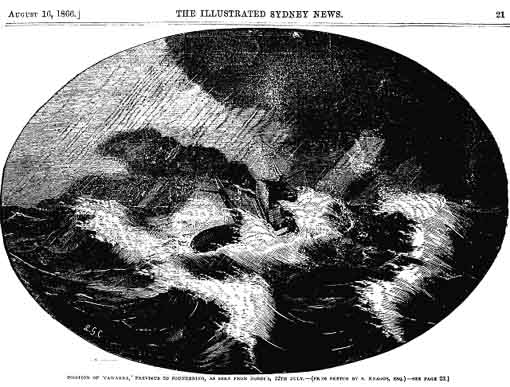

The vessel, meanwhile, was settling down fast, and no sign of a boat of any kind putting off to her assistance. About a quarter of an hour after the Cawarra began to sink her funnel fell overboard. Some of the people on Nobby's fancied they saw at the same moment several people washed overboard. It is very probable that such was actually the case. This must have been about a quarter past three o'clock, at which time the steamer had been fully an hour in a position of imminent danger, without any attempt whatever having been made to launch the lifeboat.

I was on Nobby’s when the mast fell over. It fell to windward with a slow motion. At the time great sympathy was evinced for one poor fellow whom we distinctly saw clinging to the foretop. As the mast slowly sank towards the surging waters a feeling of pity thrilled the spectators – people identified themselves with the poor fellow and a convulsive shudder and fervent "God help him" escaped them as the mast disappeared beneath a big wave. The sea past, the mast was again seen, the black form still clinging to it – another wave, and once more, for the last time, the poor fellow appeared – a sudden flutter of some fabric was observed near the black form, and all was over. It may have been his last frantic sign for help – it may have been a fluttering fragment of sail – none can tell now, but that one sad incident will never be forgotten by those who witnessed it.

By this time, some three hundred people had assembled in the vicinity of the lifeboat shed, and from that time out, group after group of people were observed to be washed off the steamer, and still no sign of the lifeboat putting off. At twenty minutes past three o'clock, the mainmast, around which some score of people could be distinctly seen clinging, was noticed to be swaying backwards and forwards. A minute or two more and over it went with its burden of human beings into the boiling, seething cauldron around.

Even at this juncture, late as it was, if the lifeboat had put out promptly, many lives beyond all doubt might have been saved. But, no! Because the proper crew were not at their posts, the boat could not be put off. The sea was now making a clean breach over the steamer, which was rapidly going to pieces. About a quarter to four o'clock the foremast, with another mass of poor drowning souls, went overboard. The bulk of the people were, of course, washed off. Two brave fellows, however, managed to cling to this spar for some ten minutes longer. As the mast was lifted up and down by the sea, the forms of the two men could be plainly seen still holding on - all, however, to no purpose. A few minutes later and a huge remorseless looking billow rolled over the wreck, and the two men on the foremast were never seen after. At last, when all but two or three poor creatures on that awful wreck had perished, the lifeboat was launched, and proceeded slowly in the direction of the wreck. Alas, it was too late.

Only a few were left on the vessel, and these had no chance of saving themselves, for the lifeboat we can positively affirm, never went within several hundred yards of the main portion of the wreck. The harrowing scene was now drawing rapidly to a close; a few minutes more only, and scarce a vestige (except floating pieces of wreck) was left standing to mark the spot where the magnificent Cawarra, steamer, with her living freight of over sixty souls, had recently floated in all her strength and glory upon the surface of the ocean. A boat belonging to the barque Maggie V. Hugg put off to the wreck shortly before the lifeboat but was unable to do any good.

The sight which I have feebly attempted to describe above was one of the most appalling it is possible to conceive of. Big, stalwart men, with brawny arms and weather beaten faces, turned from it with tearful eyes, whilst down the faces of many of the more tender-hearted of the spectators, the tears rolled thick and fast. At length, when it was all over, shortly after four o'clock, the concourse of people began to wend their way homewards.

Later in the evening, one man named Frederick Hedges who had grabbed a plank as the ship sank was eventually washed, more dead than alive, against a harbour buoy. He was picked up near the red Fairway buoy by Henry Hannell (the son of the lighthouse superintendent), James Johnson and one other, James Francis a fisherman.

Frederick Valentine Hedges, the sole survivor of the Cawarra wreck, was born at Bristol in England on 14 February 1835 and came to the colonies in December 1857 in the ship Granite City. Frederick Hedges was the son of Thomas Powell Hedges, a Bristol accountant. On 10 September 1851 Fred joined the British merchant navy. For six years Fred sailed between England and the eastern ports. He was discharged from the Granite City on 20 December 1857 and joined the Australasian Steam Navigation Company who owned the Cawarra. He was thirty-one years old and a single man when shipwrecked. He gave the following account:

"We left Sydney on Wednesday, 11 July and cleared Sydney heads about six o’clock in the evening with the wind from the East. The weather was threatening with a strong breeze blowing but the sea was not very rough. The gale increased during the night, with heavy squalls. We went with ordinary speed during the night. In the morning we set the fore-topsail to keep her steady, the sea being very high at the time.